“In the enchanted world of dreams, a killer roams free and only the author of Little Nemo can stop him…”

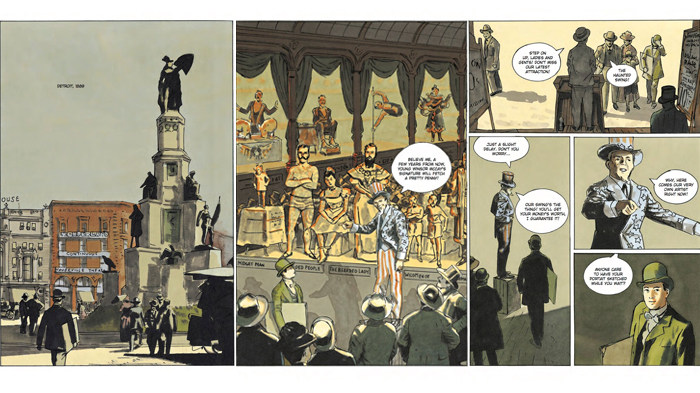

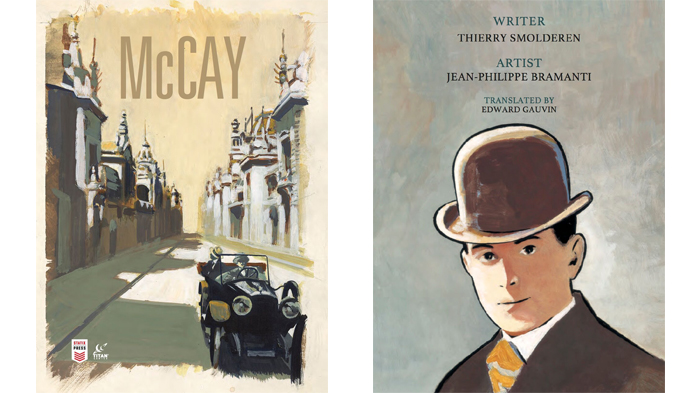

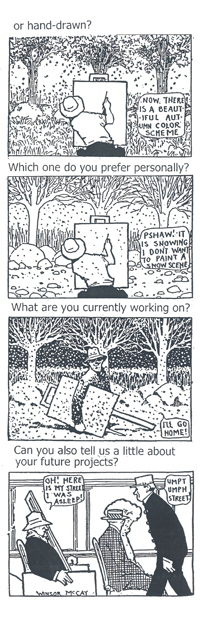

If the blurb of a book begins like this, it’s sure to catch the attention of any ardent reader like me. Such is the case with McCay, that released on 20 November. Published by Titan Comics, McCay is a beautifully crafted graphic novel by writer Thierry Smolderen and artist Jean-Phillipe Bramanti. The book is translated in English by Edward Gauvin.

McCay is the culmination of a wonderful discussion that Smolderen had with French artist, cartoonist and writer Jean Giraud (Moebius) about Little Nemo, in the middle 80s. For most of his life, Smolderen has been fascinated by Winsor McCay’s work. He said, “I was twelve when I discovered the existence of Little Nemo. At that time, I was already fascinated by old comics from the golden age, but McCay instantly became one of my gods… Giraud [too] had an unconditional admiration for McCay and I had an unconditional admiration for both of them. After that conversation, they became ‘one’ in my mind.”

McCay is a central, towering, figure in the history of the comic strip. His approach to the medium was completely different from that of his colleagues. In contrast to his colleagues who were all about comedy, slapstick, loved the mechanical world of pure action and every story was a chain-reaction, McCay was a self-made baroque artist lost in the age of Edison.

He was pursuing artistic beauty, while the other comic artists, by vocation, ignored the aesthetic dimension. The mysteries of the living body intrigued him– not in the antics of clownish, artificial ghosts- but the magnificent dreams of Wonderland, the prosaic nightmares of the Rarebit Fiend, the hunger of Hungry Henrietta, the permanent sneezes of Little Sammy – everything he drew was about the materiality and the spirituality of the human condition.

Even Gertie the Dinosaur is not a creature of fantasy. The script of the film is clever created in the way it seamlessly recaps all the essential emotions and needs of a living animal. McCay himself in a way, was a kind of cultural dinosaur who channelled very deep questions about life through the rather artificial world of comic strips and animation.

Smolderen added, “I felt both of them [Giraud and McCay] shared a kind of a superhuman intelligence of space that enabled them to transcend the two-dimensional space of the drawing paper. This is particularly noticeable in McCay’s animated movies : Gertie appears solid, completely three-dimensional in the 1913 film, anticipating computer-generated 3D animation. It started me thinking about their power in nearly magical terms. For example, I was intrigued by Giraud’s choice of pseudonym, and the way it seemed to penetrate his work. Looking closely at his work through that lens, I started noticing strange mistakes of laterality, where stuff that were at the right of a character, suddenly seemed to ‘jump’ to his left at certain dramatic moments. As if Moebius, between two images, had rotated through a superior space – a fourth dimension for a fleeting moment…When I started working on a script about McCay, I decided to ‘transfer’ this superpower to him. In the graphic novel, McCay makes sudden, involuntary trips into the fourth dimension, which gives him access to the land of dreams and nightmares.”

Smolderen has always been fascinated by the history and art of the comic strips since his early teens. He started writing articles and essays on the subject in the ’80s in Les cahiers de la bande dessinée, and very soon after that, he started writing scripts.

Since 1994, He is also been teaching script-writing and the history of the comic strip at the Angouleme School of Visual Arts while coordinating a Master and a doctoral program in partnership with the University of Poitiers. He has around forty albums of bandes dessinées to his credit,s since the middle ’80s, most of which have been translated in a dozen languages or so.

Apart from McCay, his three other graphic novels are in translation in the US. His book- The Origins of Comics, from William Hogarth to Winsor McCay was published in English by the University Press of Mississippi in 2014.

Bramanti on the other hand, studied Fine Arts in both Marseille and Angouleme. During his first year Angoulême, he met Guy Delcourt, who showed interested in his work. Bramanti always wanted to do something in the style of Little Nemo and it was one of his teachers who introduced him to Smolderen, who was already working on a project about Nemo and its creator, McCay. The two started then a cooperation and the biographical series McCay was born.

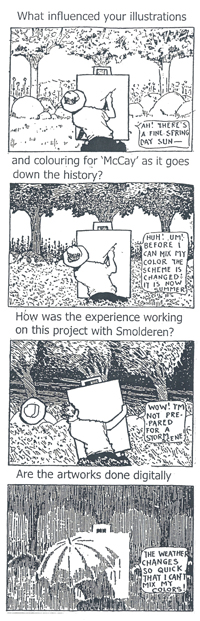

Just like his unusual style of art that looks like poetry, Bramanti is a quirky person whose answers here, have all my heart. For many years, he completely immersed himself in this long script with absolutely no regard for deadlines, making multiple versions of each page until he was satisfied. This was his first professional work, and given the subject matter, the artistic pressure he felt was much greater than any other factor.

Talking about his experience of working with Bramanti, Smolderen commented, “As an artist, Jean-Philippe is incredibly involved and he is the most amiable and laid-back guy you’ll meet in Marseilles. I must admit that I had some misgivings about his crazy, obsessive way of conducting the project, but in retrospect, I have the utmost respect for the result, which he attained with no regard whatsoever for the prosaic demands of the trade. Originally, the story was published in four instalments by Delcourt. But I am glad that the book, as published by Titan, appears in English in its proper form, as a complete graphic novel.”

Fiction gives very powerful tools to speculate about any creative process and the subject can be quite arid if the approach is in a purely scientific way. Reminiscing about what was it like to create an entire thriller around a renowned animator and artist, the writer informed, “On one hand, you have a ‘world-engineer’ like McCay, who has the ability to build a marvellous, immersive paracosm of fantasy, full of enigmatic inventions and grotesque and beautiful ideas; while on the other, cognitive sciences can only give general hypotheses about the working of the human mind. Maybe the best way to approach the enigma of the creative process is to look into the work itself, to try and find some hidden clues of what happened in the mind of the creator – in other words to interpret the most striking imagery and plot elements of the original story as oblique commentaries on the creative processes at work. The whole plot of the graphic novel is built on this principle.”

He further added, that the biographical and the purely fictive parts of the story fell perfectly into into place once he decided that the story would be about McCay meeting a dark alter ego in his early years, and that the plot would follow their parallel careers. “This young man, named Silas, would be the better, and would acquire the power of travelling deliberately through the fourth dimension. He was involved in an anarchist conspiracy and destined to pursue a long campaign of terror with the help of his fantastic superpower. Everything that concerns the interactions between the two men are pure fantasy, but everything about McCay’s family life and professional ascension in his different fields of interests are based on documented facts,” concluded Smolderen.

Putting the last touch to an academic essay about the works of Rodolphe Töpffer, whose 19th century picture stories laid the foundations of modern comic strips, Smolderen has three new graphic novels in the making, one of which is part of a thematic series drawn by Alexandre Clérisse. Atomic Empire, the first book in the series has just been published in English by IDW, and is very much in the spirit of McCay which explores the creative processes and fantastic mindscape of Cordwainer Smith, a real-life writer of science-fiction, whose life and career were even more baroque than McCay’s.

McCay has seemed to carve a mark and opened a new avenue in the genre of a thriller graphic novel around the life of a renowned artist and animator by blending history and fiction.