A storyboard is generally known as a graphic organiser in the form of illustrations or images displayed in sequence for the purpose of pre-visualising a motion picture, animation, motion graphic or interactive media sequence.

The storyboarding process, in the form it is known today, was developed at Walt Disney Productions during the early 1930s, after several years of similar processes being in use at Walt Disney and other animation studios.

The storyboarding process can be very time-consuming and intricate. Many large budget silent films were storyboarded but most of this material has been lost during the reduction of the studio archives during the 1970s. Storyboarding became popular in live-action film production during the early 1940s, and grew into a standard medium for previsualisation of films. Storyboards are now an essential part of the creative process, to an extent considered even more important than the animation film itself, forming the backbone of the feature.

Following are 10 best practices that are adapted by some of the larger and successful studios globally for their story-boarding process.

Review the film from logline, to treatment, to script with the story team and discuss and work out any issues or concerns at the get go. Take as long as you have to. Peel back the onion one layer at a time with them. Once internalised this exercise will lead to creativity, smart questions, proposed changes (including the screenplay), clear communication and team cohesion; along with a shared vision for the film which can only strengthen it. The director and producer should also be an integral part of this exercise.

Have a solid digital pipeline and clear approval processes that everyone signs-off on – have the team weigh in on it, and adjust it if need be based on their feedback. And, keep the process agile – adjust it if it’s not working for you and them. This is the only way smooth progress can be made on a long-term project, specially a feature length film.

Have complete transparency about the schedule, quotas, and overall goals for the time period. Put all production and quality documents up on the server or local drives, where anyone can get to them in case they are curious. And to foster transparency, honesty and integrity: Don’t have a secret schedule where the team is told one due date that is aggressive, while secretly thinking the team will hit another. It’s very important that everyone is on a level playing field be it an intern or an artist with 10 years under his belt.

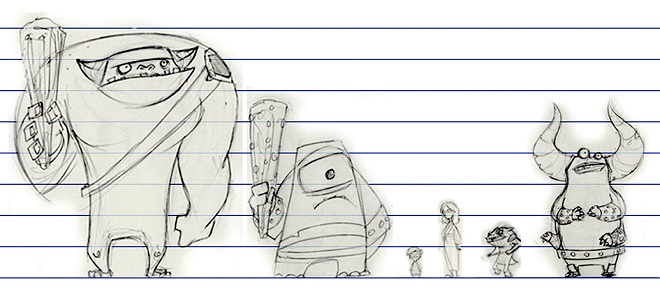

Clear criteria for the board quality – these are the various lists as well as visual representations of characters and props. Have reference material, templates, software chosen, a content management system, character short and developed and signed off on, and so on. And let the team weigh in on it – they’re responsible for hitting schedule milestones, thus need to know how intricate or otherwise must the storyboard be.

Value the law of dependencies. More dependencies equals more trouble and mistakes, and more re-do. Therefore: De-couple the representations of the characters you plan to use for boarding (simplified versions of the characters) from final character designs. Don’t make boarding dependent on final designs, as one can only reach that stage if the initial stages are ready. A blueprint can’t be made after constructing a building!

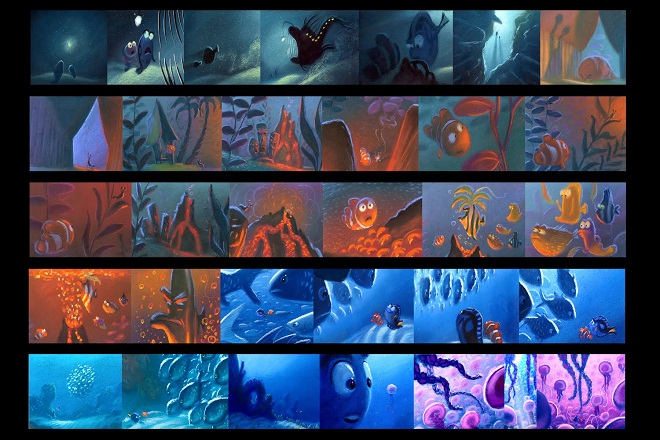

The boarding should tell the story. Use as few lines as possible to get the gist across. Make telling of the story the most important part of the job, and the time to understand the gist of the image as close to instantaneous as possible. Don’t confound the editorial process with lovely drawings that make it more difficult for you, and editorial to decide how many seconds or frames to allot for that image. Keep it very fluid and instantly readable.

Share your boards, or ideas, as thumbnails before heading into final boarding to make sure your direction is in sync with the objectives of your sequence. On that note, think of the stakeholders and run your ideas past the potentially biggest critic or most invested person in your sequence, so that there are no revisions during the final review stage. In other words, don’t work silently for days without input from others as at the end of the day it’s going to be a lobour of love involving everyone.

Celebrate each milestone! Take people out, buy lunch, cheer out loud, whatever will say “job well done!” It is very important to appreciate great work and not get too tensed when the going gets tough, there needs to be a perfect balance between applause and condemn as both are two sides of the same coin (here the feelings of your colleague).

Review the animatic of the complete film, not in pieces. We all love to look at our individual sequences before checking them in to our asset management system. But when evaluating the film with everyone present, wait until it’s all cut together. Otherwise how can you truly evaluate if an idea in Act 1 pays off well in Act 3?

Nip problems in the budding stage. Large teams can encounter any number of issues along the way. While certainly some things you can let play out, depending upon what it is, don’t think you can tackle it later. If it ripples through the film, or has a team morale aspect to it, deal with it right away. And having a very seasoned story team and a supportive producer will also go a long way in executing a successful storyboard.