Directed by Rob Letterman with a budget of $150, Pokémon: Detective Pikachu has crossed box office worldwide total of $421.8 million. MPC Film was the lead VFX studio for the VFX of the urban fantasy mystery film.

In an interaction with Animation Xpress Pokémon: Detective Pikachu VFX supervisors Pete Dionne expressed that he officially joined the team on Pokémon: Detective Pikachu after few months into pre-production, and this film was on his radar from the very beginning because of his past relationship with overall VFX supervisor Erik Nordby, and VFX producer Greg Baxter. “We all worked together on director Rob Letterman’s previous CGI creature-heavy film, Goosebumps, so it was great to be able to build upon our shared experiences of the last show to raise the bar even higher on this one,” he added.

In an interaction with Animation Xpress Pokémon: Detective Pikachu VFX supervisors Pete Dionne expressed that he officially joined the team on Pokémon: Detective Pikachu after few months into pre-production, and this film was on his radar from the very beginning because of his past relationship with overall VFX supervisor Erik Nordby, and VFX producer Greg Baxter. “We all worked together on director Rob Letterman’s previous CGI creature-heavy film, Goosebumps, so it was great to be able to build upon our shared experiences of the last show to raise the bar even higher on this one,” he added.

He revealed that MPC has completed 850 shots for the said movie which includes around 40 characters and worked upon by as many as 600 people throughout the studio itself. The primary software used for the movie was Maya, Houdini, RenderMan, Katana, and Nuke, and all artists have custom toolsets within their MPC pipeline according to him.

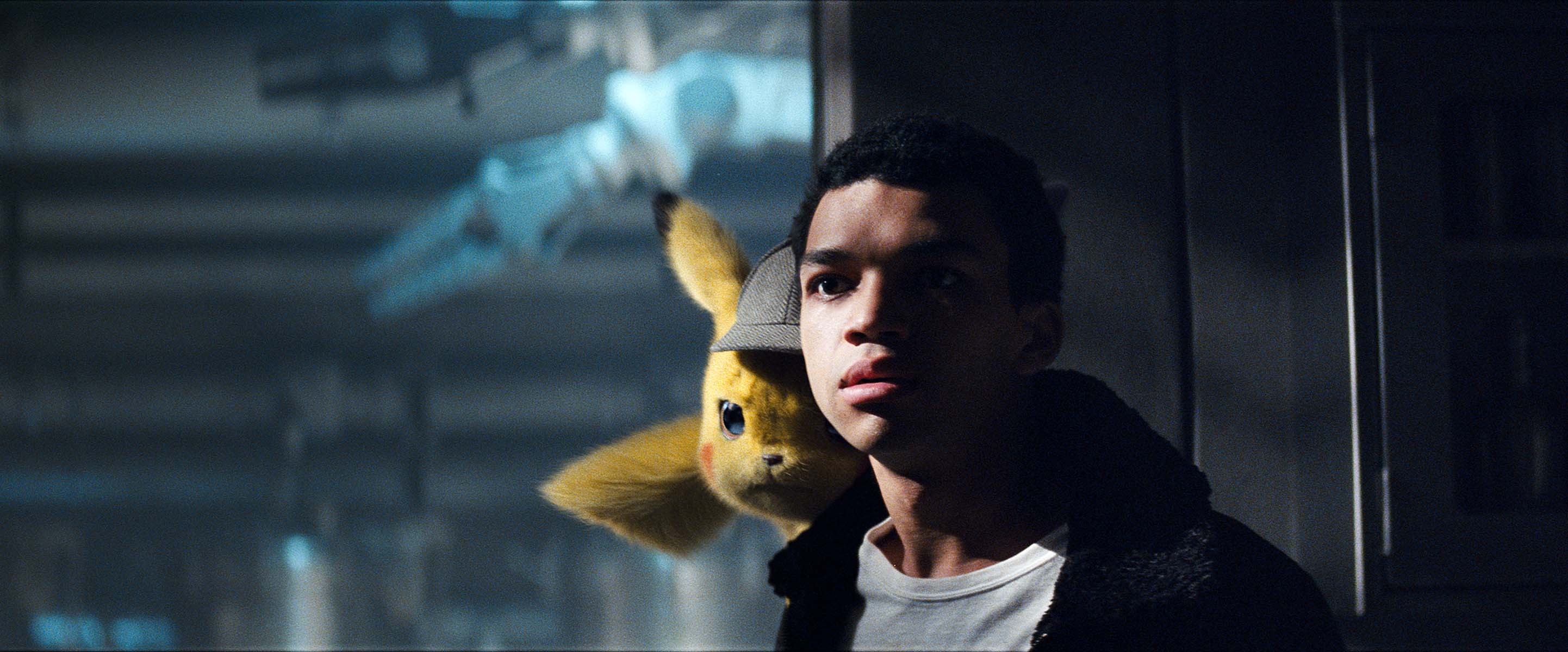

The story begins when ace detective Harry Goodman goes mysteriously missing; prompting his 21-year-old son Tim to find out what happened. Aiding in the investigation is Harry’s former Pokémon partner, Detective Pikachu: a hilariously wise-cracking, adorable super-sleuth who is a puzzlement even to himself. Finding that they are uniquely equipped to communicate with one another, Tim and Pikachu join forces on a thrilling adventure to unravel the tangled mystery. Chasing clues together through the neon-lit streets of Ryme City–a sprawling, modern metropolis where humans and Pokémon live side by side in a hyper-realistic live-action world–they encounter a diverse cast of Pokémon characters and uncover a shocking plot that could destroy this peaceful co-existence and threaten the whole Pokémon universe.

Highlighting the team’s effort for the movie he expressed that when the first trailer was released the entire team was nervous leading up to it since the film was radically different from what was expected by the fans. However the trailer had received an overwhelmingly positive response, and the excitement and anticipation rush has fuelled them to push the film across the finish line. To know more read the exclusive excerpt:

Pikachu is one of the most loved Pokemon for a mass of people? How did you approach it when you were first narrated about it?

We began the project with a tremendous amount of respect towards the original source material for the Pokémon designs, but also the challenges that we faced in transforming them into living breathing creatures in a photorealistic world. These adorable Pokémon characters all had the potential to turn grotesque very quickly with the slightest design misstep, so we dedicated a lot of time, budget, and energy to get it right.

For Pikachu, we started by gathering clips from around 30 relevant films of which had speaking non-human characters in it. We categorized each film into a few stylistic groups: on one end we had ultra-realistic characters like those in The Jungle Book and Babe, and on the other end of the spectrum we had films which embraced the cartoonish style of the characters, like the live-action Garfield and Alvin and the Chipmunks films. Across this range of styles we could really see examples of films succeeding and failing to create appealing and engaging characters. But what was more illuminating was tracking performance qualities across this spectrum, like limitations in a character’s physical performance, facial performance, comedic performance, emotional expression and engagement, and so forth. Every successful film had found its own balance of limitations and compromises, and that realisation helped us identify and prioritize our three most important goals for Pikachu. Our first goal was to create a character whose physical qualities felt like it could be a living breathing animal while staying as true to the original 2D designs as possible. Our second goal was to create a physically plausible facial muscle system that could achieve a nuanced and varied emotional performance required from a leading character, but without ever feeling cartoonish. Our third goal was to develop a style of animation which gave us a wide range of physical and dramatic performance but embracing the physical limitations of an upright quadruped animal. Having these parameters established early on for Pikachu really brought a lot of focus to our year-long design process.

How did you design all the Pokemon characters for the upcoming movie? Share us what VFX techniques you used for the movie?

On set, we had multiple Pikachu puppets and stuffies available to support the performance of the actors, as well as for integration reference for our lighters and compositors back at the studio. Typically, we would shoot with a practical puppeteered Pikachu in the shot for the first few takes of a scene, as the cast and crew develop a feel for the performance, action, and composition. Once everyone was comfortable, we would remove the puppeteer and puppet for the remaining takes, and shoot it clean, using various markers for maintaining eyelines as necessary. Once we were ready to move on, we would shoot a final pass of a clean plate without any actors in it and we would shoot chrome and grey spheres as well as 360 degree HDRI photography for reference of the scene lighting, as well as shoot an actual furried and painted latex stuffy we made of key Pokémon, for explicit reference of how our CG characters should appear in the scene. It was an exhaustive process, but it allowed us to really capture the nuance required to integrate these creatures into reality.

Will you share the work for minute design aspects that you were particular about designing Pikachu and other characters?

There is a lot of comedy and character in the juxtaposition between how adorable Pikachu looks and how crusty his personality is, and this relied on us realizing Pikachu to be as cute as possible. Fortunately, the 2D manga design of Pikachu is endlessly adorable, so we were starting from a pretty strong place. One of our stated goals was to not stray too far from this recognizable and highly revered design as we weaved complexity into this character, but through anatomical detailing as well as his motion design. Our first step in designing Pikachu was to closely match the silhouette and proportions of the 2D character design for his outer form while conforming an anatomically accurate quadruped skeletal system inside of this volume. We then layered in a plausible musculature system over top and filled the remaining volume with fat for an appealing amount of jiggle and softness. The decision to put fur onto Pikachu was controversial for some, but Pikachu as a realistic hairless creature doesn’t look that appealing, so it was an easy choice for us to make. To prevent him from simply appearing as a furry stuffed animal, we tried to get as many natural animalistic details captured in his fur as possible. We used kitten and bunny fur as our primary references, paying very close attention to the variance of details across the entire body, like density, length, stiffness, colour, and even how the different follicles transmit light. For additional detailing, we looked for animalistic features that we could add without detracting from his adorableness. For example, we embraced things like cute fuzzy bunny paws and moist kitten noses but avoided weird bits of anatomy inner ear cavity detailing and overly articulated teeth and gums. We designed his eyes as dark discs like in the anime, but added a dark brown iris, so that we could track his eyelines, as well as motivate an additional layer of caustic glinting into his eyes.

With over 1000 shots of Pikachu in this film, there was a lot of subtle variation in our CG character across the different physical states and environments. This was mostly reflected in his grooming, with multiple variations of fur cleanliness, messiness, wetness, with and without hat-hair, variations of how it reacted to wind, variations for when he activates his powers, and several more variations for workflow reasons. It was complicated to manage!

How did you handle the characteristics of the characters?

We put a lot of time and energy into motion studies for all characters early on in their development, to help solidify all of their personalities and motion characteristics. For Pikachu, we designed a battery of rendered animation tests to explore his performance in every detail possible, which is what really unlocked the character for us and defined him for the film. Early in preproduction, we sat down at a white board for an entire day and brain-stormed every possible detail we wanted to learn about Pikachu, and came up with about 50 different test shots for our animation team to explore. It was a massive undertaking which our Animation Supervisor, Jason Fittipaldi spent months executing, but it allowed us to carry an exhaustive knowledge of who our character was into production and post-production.

For Pikachu’s dialogue scenes, we explored using Ryan Reynold’s performance facial capture data to explicitly drive Pikachu’s facial animation rig, but the mapping just gave us something that was either too muted, too cartoony, or didn’t look true to Pikachu. We had much more success with traditional keyframed facial animation but enforcing a very rigid set of rules and facial expressions for the animators to follow, while transposing Ryan’s performance onto Pikachu’s face. All of Ryan Reynolds ADR was recorded with him wearing a head-mounted camera, which the animators would reference as the basis for the performance.

The backdrops are looking marvellous seems like somebody hand painted it. Share the story behind it.

Though the majority of Pokémon: Detective Pikachu was shot on location in London and Scotland, there were a few sequences that required a massive amount of CG world building, led by our Environment Supervisor Alex Clarke. The most challenging of all was our CG build of Ryme City for the climactic third act battle, and the CG Torterra forest, which required us to recreate an entire Scottish valley for our giant Torterra to occupy and the rolling forest that our characters are trapped within.

Rob Letterman’s decision to shoot his film on location in London, to double as Ryme City meant that for the majority of street-level scenes, our set enhancement was limited to skyline embellishments and adding additional Pokémon-themed CG signage throughout the city. Where things got really challenging was for all of the aerial establishing shots and the battle above the street, as the scope of this work required a full CG city. Our goal was to create a modern, bustling city, but with a much denser and taller skyline than what London had to offer.

We began by rebuilding the five-block radius of Leadenhall Street in London where the street-level parade scenes take place. This required a crazy coordinated effort of street-level photography, street-level and rooftop lidar acquisition, as well as both extensive aerial drone and helicopter photography. From all of this data, we were able to recreate a high-resolution CG version of this core to use as a base. Our next layer of development was to scatter this downtown core with around 50 additional custom designed skyscrapers, which gave us a much more congested area for Mewtwo and Pikachu to weave through during their aerial battle. Our final component was to extend the city beyond this five-block core, as we had several CG establishing shots of Ryme City from the outside looking in to create for different moments of this film.

For this, we accessed large-scale open source lidar of Vancouver and its surrounding environment to use as the footprint of Ryme City and dropped our embellished London core in the middle of it. As Vancouver lacks the density of towers which Rob Letterman desired, we then used Manhattan as an inspiration for laying out hundreds of additional skyscrapers into our digital city. With the number of buildings we needed to design and build in CG, as well as the endless amount of detailing within the streets, rooftops, and building interiors, this massive CG build took us over eight months to complete. However, with this build being so robust and fully digital, it allowed us to then turn around 200 massive shots in about two months, which was a thrill to watch come together.

The other sequence which required a massive fully CG environment was our Torterra Forest scene. Our heroes find themselves in the middle of a forest which begins to move and shift under their feet as they flee for safety, revealing at the end of the scene that they are actually on the back of a mountain-sized Torterra as it rustles around with its pals in what we previously thought was a natural valley of mountains. For this, we shot as much plate-based material as possible in the mountains and valleys of the Scottish Highlands, which established the look of our immediate digital forest, as well as serving as inspiration for how to scale a normal Torterra Pokémon up to the size of a mountain. We assembled a team of five people to travel across Northern Scotland and capture as much location data as we could through a combination of ground, drone, and helicopter photography as well as fine and large scale lidar scanning. This was crucial, as we had hundreds of assets of all scales and frequencies to create, from high-res clumps of grass to entire CG mountain landscapes.

Creating this CG forest with a convincing amount of detail and variety, required scattering millions of instances of our assets throughout the terrain. We would begin by composing our terrain from bare sculpted grounds, derived from lidar and photo scans, then we would scatter all of our grass, foliage, tree, and debris assets over top of it, using a complex Houdini workflow, to procedurally replicate the natural logic of this Scottish landscape. Every single foliage and tree asset were simulated and cached out in a variety of movements, building up a vast library of clips which were triggered based on the level and frequency of movement of the terrain, on any given shots. All of this, including the simulations, were designed with an intricate instancing workflow which then allowed us to render around 100 shots of this dense shaking forest. This was probably the most complex CG build and sequence that I’ve ever been a part of, and the team did an amazing job executing it.

What did you do to ensure that everything pans out smoothly, given the enormous scale of the project?

Pikachu was shared across all three main vendors (MPC, Framestore andImage Engine), which required quite a lot of crossover to maintain not only continuity in the look of the character, but also the nuance of Pikachu’s motion and performance throughout the film. Mewtwo also had quite a lot of crossover between MPC and Image Engine, especially in the continuity of his powers. The character development and shot execution of the other 60 supporting CG Pokémon was split across MPC and Framestore, with the majority of the Pokémon shared between both vendors. To tell you the truth, the asset sharing should have been an absolute nightmare on this show, but there was a lot of top-notch talent in all three teams executing this, so it went quite smoothly.

Which was the most challenging sequence to work on?

MPC has had several high profile and large-scale CG character films pass through our studios over the last few years, and Pokémon: Detective Pikachu has benefitted from the focused efforts that our studio has pushed into taking our character pipeline to the edge. But where we really pushed our technology and workflow to the next level was building and executing our moving Torterra forest. We’ve built forest environments at massive scales before, but this was the first time we had to then make the entire thing shake and move, and efficiently enough to execute around 100 CG shots. Nothing came easy on this specific sequence, which was part of the fun!

You’ve done creature work before, how was it for Pokémon: Detective Pikachu in terms of the scale and challenges?

Pokémon: Detective Pikachu had a much longer and focused preproduction period than I’m used to, to account for the sheer number of characters that we were tasked to design and develop. MPC created to completion around 40 out of the 60 Pokémon made for this film, but many more were developed to some level during this period. Preproduction was a very busy time trying to push through this necessary volume of character design, especially for Ravi Bensal who led the character concept development, and Character Asset Supervisor Dan Zelcs and his team who then had to build them all!

This was also the first time in a few years that I’ve had the pleasure to work on plates that were shot on 35mm film rather than digital, which is something that I really appreciated. This was a very clever choice by Director Rob Letterman to shoot on film, as well as on location in grimy overcast London, as it really helped to ground these vibrant and clean Pokémon characters into the photography and bring them into our world.

The movie although has received a mixed review from the critics but VFX wise it stood up. According to him, the movie was a cooperative effort from the entire visual effects team, and every aspect of it brings him pride. And he expects that ‘the giant Torterra sequence to be pretty epic on the big screen!’

In January 2019, before the release of the movie, Legendary Entertainment announced that a sequel is already in development and Oren Uziel has been signed as the screenwriter. Considering the VFX work of MPC in the first part, we hope the sequel of the movie is also queued for MPC.