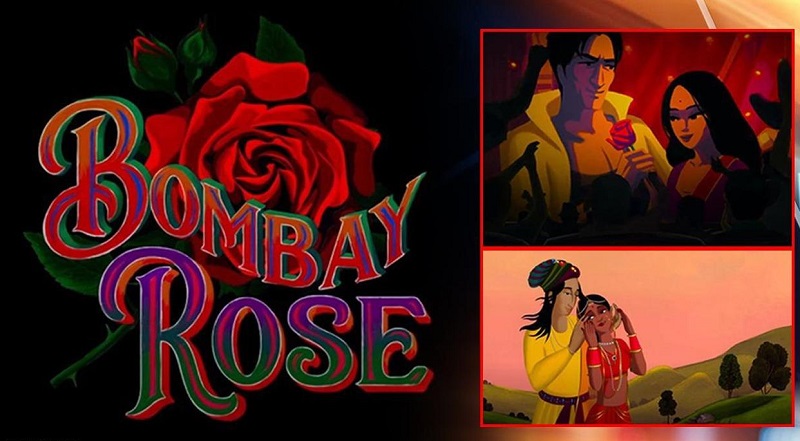

It’s been a couple of weeks since Bombay Rose released on Netflix and we’re still in awe of that film! Released on International Women’s Day, Animation Xpress had the privilege of having a heart to heart conversation with the director, animator and writer Gitanjali Rao on the animated film. As Rao said to me, “It couldn’t have been better than to release on Woman’s day and now two women are talking about it.” Read on what she had to say about the entire journey:

What inspired you to make Bombay Rose, what are those things that eventually stemmed into the 90 minute film?

Bombay Rose, like all my other short films, was inspired by the stories of the people around me. People who inhabit the city spaces which we don’t, but come across all the time – normal people going to college by buses, traveling in rickshaws, going to the center of the city from the suburbs, people who build the city, clean the city, our service providers. Unlike other cities in India, in Mumbai, all of us are all thrown together, and there’s a lot of democracy in that. There are people of different religions coming from different parts of India settling in and learning to live with each other. So I wanted to tell their survival stories who make a life out of nothing.

I’ve seen people living below the flyovers, in the streets and making these ‘gajras’ and bouquets of flowers, so these stories became interesting and I asked myself, “how do they live? How do they fall in love? What kind of films are they watching? Are they watching Bollywood? What are they learning from there?” From these stories came together the story of Kamala and Salim who fall in love in the backdrop of this city. In my mind for this story, I had to find a voice in animation. These aren’t success stories, as I wanted to talk about people who are not successful.

For me, success is a pretty relative term. We have a bad habit of identifying success with fame, money, big houses and other things. Was it easier to find this voice to counter the norms, in animation?

Absolutely. Animation is my favourite medium of filmmaking. I feel more comfortable expressing my ideas in animation, and I wouldn’t have made Bombay Rose in live-action more so because we were looking at a section of society, which is essentially poor and dispossessed. In live-action, it tends to become very close to poverty porn showing the city as it is and the fine line is generally missing. I have a very sensitive outlook towards these things and I would never like to show things in dilapidated conditions for the sake of showing it. That’s storytelling for me – what you’re seeing is miserable but beyond that, is another level of beauty, another level of human imagination, which is very rich and that richness for me has to counter the poverty of their existence. The poverty of existence comes from external factors like politics, economic structure, but the richness is real and raw. The freedom of imagination, the beauty of falling in love is real and is beautiful. When I think of a story, the medium is very clear to me right at the beginning.

The ‘rose’ plays an important symbol in the love tale. How would the love story differ if made in today’s time?

Bombay Rose would have been a very different film if I had to make it today’s time. My film is set in 2005 when the dance bars in Bombay were closed overnight, so what happens to the women who are working there – that’s the main incident in the film. Politics, socio-economic conditions of that time is what reflects in the film, like child labour, prostitution. Amidst these things, two people fall in love who never get a chance to even speak to each other before they are pulled apart and that is something which is very common in this city. We have so many untold stories. Even under grim conditions, the innocence and purity of human emotion remains phased by social conditions and that is very precious – when you feel like dreaming everything is possible in a dream. What is beautiful about Bombay Rose is that there’s always a bubbling politics which surrounds it but neither me nor my story gives into this.

Why did you choose to do it in 2D hand painted frame by frame animation?

I have a singular style of animation that I have been perfecting over the years through my short films and also because I can use this technique to push boundaries to an extent (to my satisfaction). Plus I can also animate myself and also feel, in India, the talent pool that we have in 2D animation is great, which is disappearing in the rest of the world. So it is a beautiful craft/artform which needs to be celebrated and made commercially viable to keep it alive. I come from a generation where I learnt frame-by-frame animation from the legendary Ram Mohan, so drawing every frame, painting and shooting it on a 35 mm wide screen – that’s cinema for me. The technical aspect has come in to make things easier. I use that to maintain the more classical form of still drawing because I myself can animate and can train a bunch of people. Therefore Bombay Rose looks like no other film that you’ve seen before and probably no other film can be made looking like that because it almost looks like a single artist’s way of expressing things and I love that, as it gets more realistic, almost like a painting in motion and that’s why people react to the form the way they do.

It actually looks like poetry in motion as even the intricacies, the detailing are amazing – like the beads of Kamala’s necklace. The art pieces, arches in their dream and her veil swirling in the wind, it’s so beautiful. Any comments on that?

Yes! It was done towards the end and thanks to the PaperBoat team, it wouldn’t have been possible without them. The young people were counting and working on weekends so passionately on this scene especially. So it’s overwhelming to get so much love and attention and it shows.

Did the process of animation become strenuous or challenging at a certain point of time during those 18 months with 60 artists as animation needs patience and resilience?

Not just 18 months, I would say four years of intense strenuous work. For the first one year when the contracts had been signed, I was doing the animatics of the entire film single-handedly. I was drawing every shot, every frame of the film and putting it together and then changing things. Then we started production and utilised the three months of intense training in a way that the work can also be used in the production. We had very small staff, less budget and basic machines. So, to compensate for all these, we had our hard work.

It was very challenging and difficult in the beginning till eight to nine months. We reached a crisis point where we were supposed to have finished the first 20 minutes of the film (coloured animation) according to the schedule but we had completed only eight minutes. We had no money so we had to finish it. The film would have almost stopped. So then, we all got together and decided to make this faster and still keep the quality. We had to come up with very experimental short cuts. A lot of people’s ideas and improvisations poured in to keep the quality but not spend so much time. 18 months was our target and we actually finished in the 19th month which is nothing, given an animation film usually takes five years or so. But it was crazy. There were no working hours, no extra payments for overtime, everyone owned the film. But I think it paid off in the end. It’s like after you have a child, you forget the pain of childbirth. Also 30 per cent of my staff was women who brought in a beautiful discipline, calmness and worked harder and the men in the team learned from them. It was a beautiful atmosphere.

Speaking of budgets, Indian animated projects still have a hard time to find investment backing even with Bombay Rose even though people have an appetite for animated movies. Why do you think this is still the case?

This is also the case internationally, not in mainstream animation but there’s a lot of independent animation happening even in the rest of the world where budgets are very small unlike for the biggies. The investment comes easily for Disney Pixar, DreamWorks and others because they have proved to have figured out the mechanism. In India, we compete with them despite having very small history. Indian animation started somewhere in the 90s and Disney started in the 30s. So they have a very strong history and they have arrived where they have arrived. Additionally, the country funds its own animation like in Japan and in Russia. We don’t have that in India. So I think we need 10 to 15 years of incubation of very good projects, a bunch of films. The risk-taking has to increase where people say, “I’m putting money into an animation film which might not give me my money but 10 films later I will make more money.” Netflix is doing that. It figured out that Mighty Little Bheem, which is a series, is grossing the highest amount of money like any animated series in the world. So they will have that and they will also have Bombay Rose and that is how you have the balance between doing things where you might make losses in one, but you get a good reputation and make money in another one which works in the market.

How important is the role of visual communication and arts in animation and storytelling?

My way of painting is frame by frame but what is very interesting with Paperboat was that they helped me in a very experimental way. My work was taken in the studio and designed in such a way that three different people would be doing a single frame and putting in everything that I do alone, to make it look like my work.

I can draw, I can paint and I can composite. We had a bunch of animators. A small bunch of eight or 10 who could draw amazing good line animation. They were very experienced, as experienced as me. Then you have a bunch of coloring artists who did not know animation, but were patient students to colour frame by frame as each of it required to be coloured in Photoshop on a separate layer. For this we had a bunch of younger art students who just graduated. Eventually we realised there was a gap between the two because the paint artists could not figure out where the light and shadow should come. So we got a bunch of animators to do the Shadow Maps. So we had three bunch of people doing what I do individually and a compositor would then bring all of it together to make it look like I had painted that. So it is a lot of hard work but it is the most beautiful way of maintaining painted frame by frame look.

Another fear I had was that International studios don’t really know how Indian bodies move or how Indian people do gestures. Usually, in a conventional animation film, they cast the voices, shoot and then record the film. This is another area where I experimented with in Bombay Rose. Here, we first recorded our movements, animated them and then recorded the dialogues and finally shot them. Some of the animators were good with women characters, so they were given that. Some of them were good with children, some with fight scenes, so they were given the war and the fight scenes, same with the colouring and some with details. So I had a team that became better and better while working on it. If not for Paperboat, Bombay Rose would have been a different film.

Bombay Rose is an experience and it is meant to be lived. It’s truly a visual treat and takes Indian experimental animation to another level that it long deserved.