Writing animated features is pretty much the same as writing live-action features. There

are several good books on live-action film story structure which can help the animation

writer with general story construction. I strongly suggest you read these books and glean from them the information that feels workable to you. But beware! You may find some of the concepts contradictory, which only means that different writers have found different techniques that work for them. Animation writing is not calculus, so use what makes sense to you and don’t worry about the rest. The important thing is to find anything that helps you to start creating and organising your thoughts.

Once you’ve decided upon an idea for your screenplay it’s time to write an outline. An outline lays out all of your story beats in order. You can include whatever dialogue comes to mind, but dialogue isn’t necessary in an outline.

There are three reasons to write a feature outline, all of which you should be aware of before you start writing. The first, and most obvious, is so your story is laid out for when you eventually write the script. This type of outline just lays out the story beats. It doesn’t have to be well written in terms of prose, it just has to be structured properly and complete. The second reason is that you have a well thought out story you can pitch to a prospective buyer. I’ll discuss how to pitch your story in a later post. The third reason to write a great outline is to have something to leave behind if you are pitching your story. This type of outline should be an interesting read. It’s a sales tool, and as such, anything within it that might help sell the story, and sell you as a writer, is valid.

The form of an animated feature screenplay is identical to a live-action feature screenplay.

The content is almost the same, but there are two things that are vital in an animated feature script. First, you must remember that animation is a visual medium. Thus, the story should emphasise, where necessary, unique vistas, breathtaking action, and, ideally, events that couldn’t be done in live-action (though almost anything can with CG) or would cost too much to produce live. Second, screenplays for animation sometimes have more directing in them. This is because much of what is written in animated features is often visually unusual. It can take more words to describe the unique visuals in animation than it does the regular occurrences of everyday “live-action” life.

An animated feature screenplay is written in the same format as an animated television script. Live-action features are generally considered to be one page of script for each minute of screen time. You won’t go wrong if you use this rule for your animated feature.

This is just a brief introduction to animated feature writing. There is a great deal more to it, but because the structure and content of animated feature screenplays are so similar to live-action screenplays, the best way to learn more about the subject is to study general screenwriting.

©Jeffrey Scott, All Rights Reserved

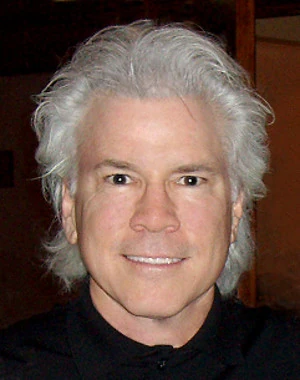

(Jeffrey Scott has written over 700 animated and live-action TV and film scripts for Sony, Warner Bros., Disney, Marvel, Universal, Paramount, Columbia, Big Animation, Hanna-Barbera and others. His writing has been honored with three Emmys and the Humanitas Prize. He is author of the acclaimed book, How to Write for Animation. To work with Jeffrey visit his website at www.JeffreyScott.tv.)

Read other articles from this series:

#1 The difference between live-action and animation writing

#3 It all begins with a premise

#4 The secret to developing your story

#5 Finding the scenes that MUST be there

#7 How to easily transform your outline into script

#8 A brief introduction to script writing

#9 How long should your scenes be?

#10 How to (and NOT to) edit your writing

#13 The importance of communication

#17 Assuming the point of view of your audience