Continuity means an uninterrupted succession or flow; a coherent whole. In script writing, it means that there are no discrepancies in the cutting from scene to scene, so that everything flows smoothly for the viewer, both visually and conceptually. Thus, continuity problems are really just problems in logic.

An example of a gross continuity error would be if a character had their foot seriously injured in one scene and the following day in the next scene was shown dancing as if nothing had ever happened.

Continuity errors are easier to make in animation than live action because in animation (especially of the squash and stretch variety) we often stretch the laws of physics. By doing so, we set ourselves up to be inconsistent with these new rules. For example, if you describe a character who flattens when a piano drops on him, you’d better not have a safe fall on him in the next scene and bounce off his head.

Continuity errors are one of the most obvious signs of an inexperienced writer. Some of them are blatant, as with the injured foot. But some can be very subtle and thus hard for the inexperienced writer to spot. For example, you might have a superhero character in one scene straining to lift a car off someone, then, in a later scene he pulls up an oak tree with ease. In fact, pulling up an oak tree would be ten times harder than lifting a car. Four big men can lift a small car. It takes a tractor to uproot a tree.

This at once tells you that in order to avoid continuity problems you have to understand the subjects you write about. It helps to know about physics and other natural laws, as these are always present in real stories. It also helps to understand the unnatural laws created for squash-and-stretch cartoons.

Continuity errors are not just related to action. There can be errors in the continuity of characters. A character who is a jerk in one scene should not be a nice guy in the next unless something significant has changed him.

A simple way to ensure proper continuity is to read one scene at a time, asking yourself the question – “Is there anything about what just happened in this scene that doesn’t make sense in light of what happened so far in the story?” Your ability to answer this question will be governed by your knowledge of what you are writing about and your ability to be logical. If you find a continuity error you simply have to adjust an earlier or later scene, or in some cases both.

When you become experienced with continuity you can read through a script rapidly and the continuity errors will stick out like sore thumbs.

©Jeffrey Scott, All Rights Reserved

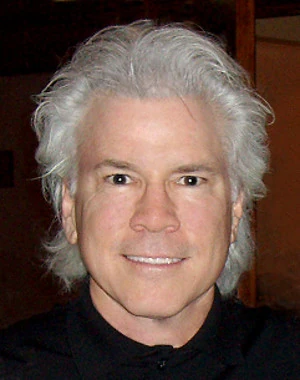

Jeffrey Scott has written over 700 animated and live-action TV and film scripts for Sony, Warner Bros., Disney, Marvel, Universal, Paramount, Columbia, Big Animation, Hanna-Barbera and others. His writing has been honored with three Emmys and the Humanitas Prize. He is author of the acclaimed book, How to Write for Animation. To work with Jeffrey visit his website at www.JeffreyScott.tv.

Read other articles from this series:

#1 The difference between live-action and animation writing

#3 It all begins with a premise

#4 The secret to developing your story

#5 Finding the scenes that MUST be there

#7 How to easily transform your outline into script

#8 A brief introduction to script writing

#9 How long should your scenes be?

#10 How to (and NOT to) edit your writing

#13 The importance of communication