Voodoo Highway Music Group, known for composing music for children’s television, is responsible for composing the music behind the beloved show PAW Patrol and even created a song during lockdown called Wash Your Hands, that teaches children the importance of good hand hygiene and includes a 20 second chorus, easy to memorize for kids to sing along while they wash their hands.

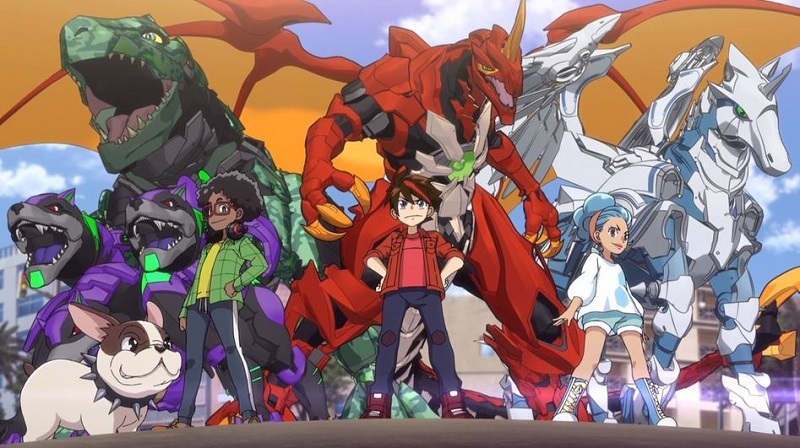

They have also scored music for the the PBS series Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, where they reimagined the classic Won’t You Be My Neighbor theme song for the series, transforming it into a tune that exemplifies Daniel Tiger’s journey through his own neighborhood. Voodoo has also scored fun, exciting music for a number of other series including Cartoon Network’s Total DramaRama and Bakugan: Armored Alliance, which they would also love to chat with you about.

Members- Graeme Cornies, James Chapple, and Brian Pickett have penned music for many kids’ shows and are all fathers themselves. Their goal is to use music as an essential tool for furthering learning and growth, and have written songs teaching kids about all aspects of life, from welcoming a new baby to the family to staying safe at home. Their music has been helping parents during this time who may be looking for more ways to entertain their children during this time of homeschooling and staying inside. They speak to Animation Xpress, on the journey, experience and more.

How was the overall experience working on animated projects like Daniel Tiger’s Neighborhood, Paw Patrol and the Total Dramarama?

JAMES: All three of those shows were pretty much dream projects for us to work on, and really a lot of fun. It always helps when a show you work on becomes a hit, as it forces you to really “up your game” as a composer. The thought that there are millions of people watching sort of burrows its way into your subconscious, and creates a quality barometer that you want to meet, which is a really great motivator to produce the best work you possibly can. So, overall, these shows have been a total blessing for us.

The challenge on these shows, which is typical of most shows we work on, is trying to nail down a sound (or musical palette) for the series. This happens at the beginning of each show and involves a lot of back and forth between us and the producers, often with many trips back to the drawing board. These shows were no different, especially Daniel Tiger as the songwriting component of the show required a lot of planning and pre-production that was based on firm Early Childhood Education research. This hard work really paid off though in my opinion, as the songs on Daniel Tiger are one of the aspects that set it apart from similar shows, and is clearly a hit with both kids and parents.

How is composing for animation different from composing live-action projects?

GRAEME: It really depends on the show, but I would say that generally, animation plays out at a much faster pace. Rather than developing a musical idea over the course of a whole scene the way you might in a live-action drama, we’re often setting up and paying off jokes every seven to 15 seconds. Even in shows that are less comedic and more dramatic, we’re usually musically following each turn in conversation closely as it plays out. On shows that have educational goals, we’re often doing what we can musically to reinforce things that our youngest viewers might want to pay attention to in order to grasp a concept. So I would say that the result isn’t the kind of thing that you typically find on a major film soundtrack, but it does have a style and craftsmanship that is unique to animation.

What are the points that you keep in mind when you are composing an animated project, as there are so many challenges in terms of edits and re-edits and changes in the script, dialogues and even the entire setup?

BRIAN: We’ve been brought on to projects both in the very early stages, (such as the scripting and storyboarding phases) as well as in the very late stages, (as in the first episode final mixes in three to four days). Both experiences have challenges and benefits. When you do start with a series in the very early phases, there can be a lot of twists and turns along the way.

I feel that the key to navigating these twists and turns is to have a music editor on your team that is creative, adaptive, funny, and doesn’t miss a thing. We are fortunate to work with Jason Turriff, who is one of the best in the industry. He will retime our music throughout cuts, and repurpose our score in ways that are funnier than how we intended. It helps that he also has a great sense of humor.

We wrote the score for the 2016 version of the George of the Jungle TV series. They were very ambitious and wanted to finish 2 X 22 min episodes every week. We are very quick, but that pace would have been tough even for us, so we ended up getting an early start and scoring the series to the storyboards. When the completed episodes came out, Jason retimed all of our music and sent it off to the mixer. We couldn’t have done it without him.

We wrote the score for the 2016 version of the George of the Jungle TV series. They were very ambitious and wanted to finish 2 X 22 min episodes every week. We are very quick, but that pace would have been tough even for us, so we ended up getting an early start and scoring the series to the storyboards. When the completed episodes came out, Jason retimed all of our music and sent it off to the mixer. We couldn’t have done it without him.

Lastly, we’ve scored almost 70 seasons of TV and been through some fairly insane situations. From working impossible hours, dissecting and reworking songs in the eleventh hour, scoring and rescoring the same scenes over and over again. We’ve been through the fire, and have a solution for almost every seemingly impossible situation.

Is it more difficult to compose music for an animated feature film or an animated series? Which requires more attention and dedication?

JAMES: We’ve had the pleasure to compose for a few long-form versions of the shows we work on, and there is a different way we approach these movies as opposed to a regular episode. The main challenge is that the quality of a long-form episode (or “movie” as they are referred to during production) is typically higher from all angles: the stakes are higher, the adventure is bigger, the action is more intense, and so on. From a musical perspective we try to match this uptick in quality by spending more time on cues, and oftentimes incorporating larger orchestral arrangements on top of the typical instrumentation. This helps create a larger, more cinematic tone, so the audience is aware that indeed this is not an average episode. Also, we tend to score the entirety of the movie, rather than rely heavily on previously composed libraries or scoring only selected scenes. This means these movies are quite a lot more work than an average episode, but we enjoy the challenge and the results are something we’re often very proud of. It’s always a very pleasurable and rewarding experience overall, and we hope to move into doing more feature film scores in the future.

How has working on animated projects changed since the pandemic started? With most people working from home, was it a challenge to do music recordings or voiceovers remotely? How did you manage?

BRIAN: We do have a studio/office downtown, but we’ve had strong ‘working from home’ games since we all started having kids around 10 years ago. When the insane hours do start, it’s great to be able to have dinner with your family, help with bedtime, and then run downstairs and get back to work. If I had to be away from my family during the busier times, I would have burned out long ago.

For that reason, the three of us were already well-equipped mentally and process-wise to work from home when the pandemic struck. The one thing that did change was the in-person voice and instrumentalist recording. When the first stay at home order hit, we worked with a local music store to provide a consistent and easy setup recording system (microphone, audio interface, and so on) that was dropped off to the talent. There were a few kinks but they all got the hang of the technical stuff quite quickly.

Because a series like Daniel Tiger has 80+ songs per season, with usually four to 10 cast members singing across them, it can get a bit hard to keep track of everything. We have a Music producer/Engineer/Vocal coach named Rachael Johnstone who holds all that down. She keeps track of Revisions, and who needs to record, as well as final mixing of all the songs. These days, she spends quite a bit of time on FaceTime, Skype, and Zoom recording various actors singing from their homes.

What role does music play in bringing the magic to life of any story?

GRAEME: I think when we’re watching TV, most of us are primarily focused on what we’re seeing. That makes sense of course, but anyone who has ever watched animation without music will know just how much it adds to the overall experience. It provides the subtext for what the characters themselves can’t or don’t say. It can distil the feeling of a place, but most of all, music has the ability to bring back strong feelings in an instant, the way a scent can bring back a flood of memories from another time. I often feel like music can temporarily resurrect the whole feeling of watching a show that you loved and even the feeling of watching it at whatever age you watched it.

As music composers and sound designers, where do you draw inspiration from?

JAMES: I get inspired in different ways depending on which project I’m working on. For example, the music on Daniel Tiger is a totally different ball game than the music on Bakugan. Ultimately though, I’m drawing upon my own past musical experiences and tastes, whether it’s the classic Fred Rogers’ intimate jazz piano sound for Daniel Tiger, or the Electronic Rock combined with a Star Wars-like score for Bakugan. I will say I’m heavily influenced by the great film composers I grew up listening to like John Williams, James Horner, Danny Elfman, Michael Kamen and many others. But in equal measure, I have a wide background of playing in different bands and enjoy listening to a wide variety of different genres. Ultimately I’m able to throw all of these tastes and experiences into the well of inspiration, and selectively draw upon them depending on the direction the particular show I’m working on takes me.